Entwurf: Bremen – Galopprennbahn

Prof. Klaus Schäfer, November 2016

(English translation subsequent)

Skizze: Klaus Schäfer

Die Potentiale für ein Wachstum der Städte liegen im suburbanen Raum der Städte. Hier ist das wesentliche Reservoir im Ringen um eine nachhaltige Stadtstruktur zu sehen. Denn die ‚Stadt der kurzen Wege‘ ist das Ideal einer ressourcenschonenden, engen Verknüpfung verschiedener Nutzungen und sozialer Gruppen. Allein in dieser Zielsetzung ist der Fortschritt zu einer sinnvollen Stadtgestaltung erkennbar. Jegliche neue Entwicklung steht immer im Vergleich zum Vorhandenen, dessen Reserven schon lange begrenzt sind.

Der Tagesspiegel, 20. September 2016, Artikel: „In den Städten wird es eng“ von Sarah Kramer (Foto: Bernd von Jutrczenka/dpa)

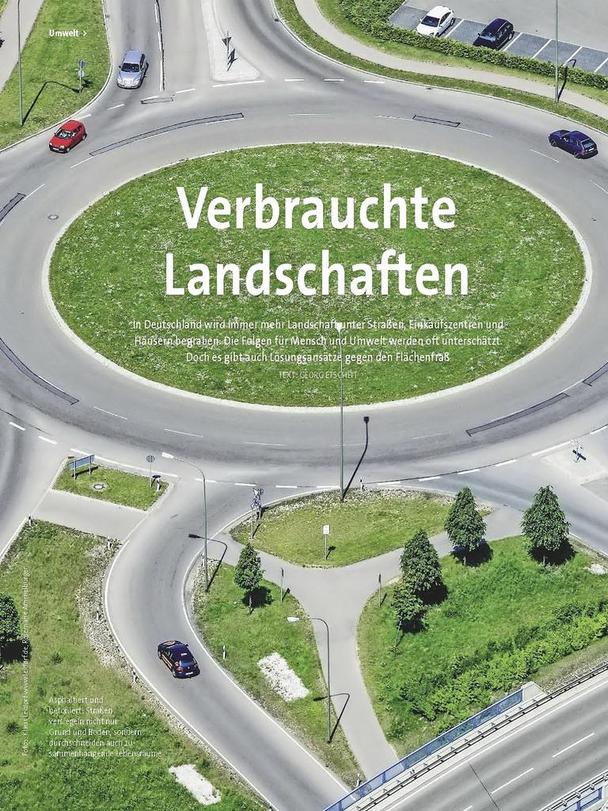

Natur, Heft 6.2016, Artikel: „Verbrauchte Landschaften“ von Georg Etscheit (Foto: Klaus Leidorf)

Der Ort

Die projektierte Auflassung einer Galopprennbahn in Bremen bietet Anlass, nach grundsätzlichen Positionen der Stadtentwicklung zu suchen. Das Gelände von 45 Hektar liegt im typischen Weichbild einer Großstadt in gut fünf Kilometer Entfernung zum westlichen Stadtkern. Der paradigmatische Begriff einer ‚Zwischenstadt‘ für diese suburbane Lage wurde von dem Stadtplaner Tom Sieverts Mitte der 1990er geprägt. Als ein fortschrittlicher Terminus, der die Eigenständigkeit und ‚Schönheit dieser Orte‘ über ihren Nutzwert definierte, führte er auch damals schon zu Kontroversen. Mit zunehmender Abkehr von der autogerechten Stadt, der Hinwendung zur ökologischen Stadtentwicklung, aber auch der kulturellen ‚Renaissance des Städtischen‘ erscheint heute jegliche positive Konnotation dieses Begriffs ermattet.

Das Areal der Galopprennbahn wird im Norden von der Neuen Vahr, einer Modellsiedlung von Ernst May aus den 1950ern, gesäumt. Im Osten schließt ein weites Einfamilienhausgebiet an, direkt angrenzend im Südosten liegt das Mercedes-Benz-Werk von Bremen. Südlich jenseits einer vierspurigen Trasse, findet sich ein Wechsel aus Großmärkten und Kleingärten, im Westen schließt die Gartenstadt Vahr den Reigen.

Die Galopprennbahn – obwohl mit 150 Jahren die älteste vorhandene Raumfigur – erscheint, wie alle anderen Anrainer, völlig beziehungslos zur Nachbarschaft, die strukturell jeweils nur ihrer Eigenlogik folgen, gleichsam wie auf einem leeren Blatt Papier entwickelt. Die obligatorische Spurensuche mit dem Ziel, für das zu Planende an Vorhandenes anzuknüpfen oder gar natürliche Wurzeln zu finden, brächte immer nur die Artefakte menschlicher Spuren hervor, um wiederum etwas Neues zu schaffen.

Neue Vahr, Postkarte aus den 1960er

Das Städtische

Eine Grundformel lässt sich definieren als: Das Zusammenführen von unterschiedlichen Menschen in ihrer Tätigkeit und ihrem Sosein (wie sie sind) auf dichtestem Raum in einer Stadtlandschaft, die fähig ist, auf wandelnde räumliche Bedürfnisse reagieren zu können.

Zur Vorrausetzung hat dies Funktionen, die nicht unbedingt sofort erkennbar sind, aber dennoch fundamentale Bedeutung haben. Mit einer Parzellierung wird eine Grundeigenschaft für die Entwicklungsfähigkeit der Stadt als ein beständiger und unabhängiger Prozess geschaffen. Eine hinreichende Parzellengröße erzeugt Maßstäblichkeit für Eigentum und damit Verantwortung, im Sinne von Identität und Identifizierbarkeit.

Mischung als unabdingbare Qualität für neue Quartiere, muss sich durch Mischung von Nutzungen und Sozialstruktur ausprägen. Bei der Nutzungsmischung geht es um die enge Verknüpfung von Arbeiten und Wohnen, genau in dieser Reihenfolge. Nach Hanna Ahrendt liegt in der Beziehung von Arbeit in ihrem Identität stiftenden Charakter und dem Dasein des Menschen innerhalb der Bürgerlichen Gesellschaft, eine existentielle Bedeutung. Eine Grundlage dieses ‚tätigen Lebens‘ sieht sie in der urbanen Verklammerung von Öffentlichem und Privatem.

Ökonomisch wird durch eine Nutzungsmischung die positive Voraussetzung für eine Stadt der kurzen Wege geschaffen. Die Mehrfachnutzung schafft erst die Frequenz im Gebrauch von Straßen und Wegen, die zu einer Qualität des Öffentlichen beitragen. Soziologisch wird so erst der Anlass zur Begegnung geschaffen. Es entsteht damit die Teilhabe an der Arbeitswelt Anderer, Kinder haben einen ganzheitlichen Zugang zur Welt der Erwachsenen.

Eine soziale Mischung findet ihren Idealzustand in einer engen Nachbarschaft unterschiedlicher Schichten und Milieus. Hierdurch werden Anteilnahme, Vorbildcharakter, sozialer Abgleich und Austausch befördert. Der Ausgleich von Gesellschaftskonflikten, als selbstverständliche Voraussetzung des Städtischen, kann somit niederschwellig erfolgen.

Siedeln als Sinnstiftung

Neben den strukturellen Grundvoraussetzungen für eine urbane Setzung ist in der Betrachtung gesellschaftlicher Rückwirkungen ein spezifischer Aspekt hervorzuheben. Soziabilität steht für die Menschenfreundlichkeit einer Ansiedlung. Im idealen Sinne wird diese Eigenschaft des Städtischen von einer ausgewogenen Mischung aus privat und öffentlich, Nähe und Distanz, persönlich und anonym befördert. Auch die Wahrung des Anonymen ist hier eine wichtige Voraussetzung. Teilaspekt hiervon ist der Umgang mit Fremden und das Lebensgefühl des Fremden – das Thema der Migration: Ankommen und eine Existenz gründen steht in einem geradezu archaischen Zusammenhang zum Städtischen und gehört zum Gründungsmythos der urbanen Gesellschaft.

Anlass, das Thema Migration aufzunehmen, ist die aktuell in bedrohliche Schieflage geratene öffentliche Diskussion, Flüchtlinge nur als Versorgungsproblem zu betrachten. Aus dem Ansatz, Migration als Chance für die Gesellschaft zu begreifen und auch als eine fortwährende Aufgabe für die Stadtentwicklung zu akzeptieren, soll ein weitereichendes Konzept entwickelt werden. Mehr noch ließe sich hier unsere Planungskultur weiterentwickeln, eine Bekräftigung finden, bisherige Gestaltungshindernisse aufzulösen.

Im Leitmotiv der ‚Arrival City‘ steckt die Erfahrung, wie Migration sich als fruchtbarer Bestandteil einer Gesellschaft erweist. Es wird aber auch ein wertvoller Aspekt der Selbständigkeit als eine strukturelle Eigenschaft von Stadt deutlich, die nicht nur für das Thema Migration Bedeutung hat, sondern über das Thema Integration noch hinausgeht. Gibt es eine Stadtstruktur, die eigenständiges Handeln hervorruft, möglich macht oder gar unterdrückt? Das betrifft nicht allein das Thema der Migration, sondern birgt eine Frage für die Stadtgesellschaft insgesamt. Diese ureigene Eigenschaft der Stadt gilt es zu diskutieren.

Amnesty Journal 08-09/2016, Lena Reich: „Engagiert Euch“, Interview mit Anna Scheuermann über die 15. Architekturbiennale (Fotos: Tadeuz Jalocha, Cristobal Palm: Häuser von Alejandro Aravena, ELEMENTAL)

Die Zwischenstadt

Lässt sich die Zwischenstadt nachhaltig – nachhaltig im gesellschaftlichen und ökologischem Sinne – verändern? Die gesellschaftlichen Aspekte sind den ökologischen als Kriterien voranzustellen. Hierzu wäre eine Konsolidierung im Sinne einer städtischen Verdichtung an strategisch wichtigen Standorten sinnvoll. Im weiten Feld suburbaner Lagen ließen sich neue Kulminationspunkte in Form einer städtischen Setzung bilden, die als urbane Zentren, ähnlich den bisherigen Kernstädten, dienen. Sie sollten einen Ausgleich schaffen zum gegenwärtigen Entwicklungsdruck auf die ‚Altstädte‘. Mit der ‚Renaissance der Innenstädte‘ verbindet sich zwar eine erfreuliche Hinwendung zur ‚Stadt der kurzen Wege‘, doch diese Ressource erweist sich gerade als nur begrenzt verfügbar.

Vieles, das zur Stadt gehört, ist in der Zwischenstadt schon vorhanden. Es muss nur zusammengeführt – gebündelt – werden zu etwas Größerem, anerkanntermaßen, das, was in unserer Kultur mehr ist als die Summe seiner Teile: die Stadt als Artefakt, das Ergebnis eines generationenübergreifenden Prozesses (!).

Tübingen, Französisches Viertel, Aixer Straße (soziales und nutzungsgemischtes Neubauquartier auf parzelliertem Baugrund für Baugemeinschaften seit 1995), Deutscher Städtebaupreis 2001, Europäischer Städtebaupreis 2002, DIVA-Award 2004

Das Podium

Im Symposium sind drei der hier füreinander bedeutsamen Themen in Vorträgen herausgearbeitet und zur Diskussion gestellt:

Andreas Feldtkeller (Französisches Viertel, Tübingen) hat als Stadtplaner ein bisher in Deutschland einmaliges Neubauviertel geschaffen, in dem eine ‚selbstverständliche‘ Mischung sozialer Art und der Nutzungen gelungen ist.

Susanne Hauser (Ort und Identität) befragt die kulturellen Verhältnisse in der Stadtentwicklung zum suburbanen Raum.

Iris Reuther (Senatsbaudirektorin Bremen) stellt Bremen mit seinen gegenwärtigen Stadtentwicklungsprojekten vor und Diskutiert mit Andreas Feldtkeller über Möglichkeiten einer nutzungsgemischten Stadtstruktur in der Neuplanung: Wie haben Sie das gemacht?

Doug Saunders berichtet als Autor des Buches ‚Arrival City‘, einer weltweiten Analyse des Themas Migration, von seinen Erfahrungen, insbesondere über den positiven Einfluss einer auf Integration eingestellten Gesellschaft.

Julian Schubert, als Mitgestalter des Deutschen Pavillons, mit dem Thema ‚Arrival Country‘ bei der Architekturbiennale in Venedig 2016, stellt typologische Ansätze und Beispiele der Architektur hierzu vor.

Organisation

Hochschule Bremen, Klaus Schäfer (Moderation), Anja Link, School of Architecture Bremen, Neustadtswall 30, 28199 Bremen

bremer shakespeare company

Das internationale Symposium fand am 2. November 2016 auf der Bühne der bremer shakespeare company statt. Die Veranstaltung wurde aus Mitteln der Forschungscluster-Förderung durch die Hochschule Bremen finanziert.

Podium: Julian Schubert, Doug Sanders, Andreas Feldtkeller, Iris Reuther und Susanne Hauser

Symposium – Restructuring the Zwischenstadt

The city’s potential for growth lies in its suburban areas. They may be considered the main reservoir in the struggle to achieve a sustainable city structure, because the ‘city of short distances’ is the ideal model for promoting the resource-efficient, close linkage of different uses and social groups. The mere act of setting this objective is itself a sign of progress towards meaningful urban design. A new development always unfolds in comparison to the existing situation, whose reserves have long become limited.

From an urban landscape, whose superficial appearance illustrates the consumption of landscape, we must succeed in creating something positive, something constructive. That means building something at this suburban location that surpasses the existing fabric and brings about a reinterpretation, in the sense of a re-evaluation of what we have found there. This restructuring of the Zwischenstadt (Sierverts: “in-between city“) has the goal of providing an equivalent counterpart to the city.

Luftbild Google Earth: oben rot markiert die Lage des Alvar-Aalto-Hochhauses / tagged in red skyscraper from Alvar Aalto

The Location

The proposed abandonment of a racecourse in Bremen offers an opportunity to explore fundamental urban development strategies. The site, measuring 45 hectares, is located in a typical metropolitan periphery at a distance of at least five kilometres from the western edge of the city centre. In the mid-1990s, urban planner Tom Sieverts coined the paradigmatic term Zwischenstadt for this kind of suburban location. As a progress-oriented term that defined the autonomy and “beauty of these places” in terms of their utility, it aroused controversy even at the time. With the growing move away from the car-friendly city and towards ecological urban development, as well as the cultural ‘Renaissance of the urban’, any positive connotation of his term now seems jaded.

Neue Vahr: Ideal einer Stadtlandschaft / the ideal of a city landscape

The racecourse grounds are bordered to the north by Neue Vahr, a model housing development designed by Ernst May in the 1950s. A large estate of detached houses lies to the east, with the Bremen factory of Mercedes-Benz to the south-east. Southwards, on the other side of a four-lane road, there is a mixture of wholesale markets and garden allotments, while in the west a garden suburb, Gartenstadt Vahr completes the picture.

The racecourse, which at 110 years of age is the oldest existing spatial construct, nonetheless seems to have no relationship whatsoever to the neighbourhood. In this it is like all of the other properties, which as regards structure follow only their own logic, as though laid out on a blank sheet of paper. The obligatory analysis of the locality in the hope of finding some feature – or even a natural characteristic – to latch onto in subsequent planning, would turn up no more than the artefacts left by human activity, only to create something new in turn.

Urbanity

A basic formula for creating urbanity could be stated as: bringing together people who differ in their activities and their Suchness (how they intrinsically are) at very high density within a built-up landscape that is capable of responding to changing spatial needs.

Its prerequisites are functions that may not be recognisable at first glance, but are nevertheless of fundamental importance. The subdivision of land into parcels creates a characteristic that is fundamental to the city’s ability to evolve in a constant, independent process. The existence of parcels of sufficient size generates an appropriate scale for the ownership of property and with it responsibility, in the sense of identity and identification.

Gelungene Integration von produzierendem Gewerbe: Volker Staab, Nya Nordiska, Dannenberg 2008 – 2010 / successful integration of industries

Diversity, as an essential quality of new city quarters, must be characterised by mixed use and mixed social structure. The mixture of uses is a matter of close linkage between the workplace and the home, in precisely this order. According to Hanna Ahrendt, the relationship between work, in its identity-forming aspect, and the individual’s presence within civil society is one of existential significance. She sees the urban interlocking of public and private as a foundation of this “active life”.

Economically, a mixture of uses fulfils the positive condition for a city of short distances. Multiple use ensures that roads and paths are frequented sufficiently for them to help to generate a public quality. From the sociological viewpoint, it is this that first provides the catalyst for encounters. With it comes involvement in the working world of others, while children gain all-round access to the world of adults.

A social mixture achieves its ideal state in a closely knit neighbourhood containing different classes and milieus. This promotes compassion, roll-model identification, social comparison and interaction. The settling of social conflicts, as a natural precondition of urban life, can therefore take place at a low threshold.

Settling and a Sense of Purpose

In addition to the structural preconditions for an urban development, any consideration of the social repercussions contains one particular aspect that deserves special attention. Sociability is an indicator of the amenability of a settlement. In an ideal sense, this characteristic of the urban situation is promoted by a well-balanced blend of private and public, closeness and distance, and familiarity and anonymity. The preservation of anonymity is also essential to it. One aspect of it is the treatment of foreigners and the foreigner’s impressions of life here: the topic of migration. The narrative of arriving and establishing a foothold has an almost archaic association with the city and it forms part of the founding myth of urban society as such.

The reason for raising the subject of migration is the current state of public debate, which is dangerously lopsided in that refugees are considered merely as a logistical problem. The intention is to develop a more far-reaching concept on the basis that migration should be understood as an opportunity for society and accepted as an ongoing component of urban development work. Moreover, doing so furnishes an opportunity to upgrade our planning culture and to find an affirmation for dismantling previous obstacles to design.

Mark Brandwein: Bebauungsvorschlag für das ehemalige Flugfeld Tempelhof, Berlin / proposal for an urban site on Tempelhof the former airfield, Berlin

Inherent in the leitmotif of the ‘arrival city’ is the experience of how migration turns out to be a productive element of a society. A valuable aspect of self-reliance, as a structural feature of the city, also becomes apparent. This is important not only in connection with migration, but integration and beyond. Is there an urban structure that induces independent action – or enables, even suppresses it? The question is relevant not only to the issue of migration, but also to urban society as a whole. It is this unique property of the city that we intend to discuss.

Zwischenstadt

Can the Zwischenstadt – the ‘in-between-city’ – be changed sustainably in social and ecological respects? In establishing the criteria, social aspects should be given precedence over ecological ones. Consolidation, in the sense of urban densification at strategic locations, would be an expedient means of bringing about this change. New culmination points of an urban character could be created at a broad range of suburban locations. These would serve as nodes in a way similar to conventional city centres. They should thus relieve the current pressure of development on historic city centres. Although the ‘Renaissance of the inner cities’ is associated with a positive trend towards the ‘city of short distances’, at the moment the latter is turning out to be a resource of limited availability.

Much of what goes to make up the city is already present in the Zwischenstadt. It just needs to be brought together – bundled – into something bigger, which in our culture is accepted to be more than the sum of its parts: the city as an artefact, the product of a cross-generational process!

„La beauté de l' ordinaire“ (LABEL architecture, Architekturbiennale Venedig 2006) war der Titel des belgischen Pavillons, Seite 6 des Begleithefts / LABEL architecture shows the suburban realm in Belgium

Speakers

At the symposium, three related topics of importance in this context will be explored in lectures and offered for discussion:

Andreas Feldtkeller (‘French quarter’, The Tubingen Model) is a town planner who has created a new district that is unique in Germany to date, with a successful and natural mixture of uses and social backgrounds.

Susanne Hauser (Place and Identity) asks for the cultural aspects of our view on the development of the suburban realm of the cities.

Iris Reuther (chief of the urban planning administration Bremen) gives an overview of Bremen and its recent urban devolvement projects and talks with Andreas Feldtkeller about the introduction of mixed use in construction areas: how have you done it?

Doug Saunders, author of the book Arrival City, a global analysis of the issue of migration, talks about his experiences, in particular about the positive influence of a society that is attuned to integration.

Julian Schubert, co-designer of the German contribution (on the theme of ‘Arrival Country’) to the Architecture Biennale in Venice 2016, takes a typological look at examples of architecture associated with the subject.

Organisation

Hochschule Bremen, Klaus Schäfer (chair), Anja Link, School of Architecture Bremen, Neustadtswall 30, 28199 Bremen

bremer shakespeare company

This international symposium took place at November 2nd 2016 on the stage of the bremer shakespeare company. The event was sponsored by the research cluster foundation of the Hochschule Bremen.

Translation: Richard Toovey