Irene Pace, Januar 2016

Happy City: Transforming Our Lives Through Urban Design is a 2013 book written by Charles Montgomery.

The author is a Canadian writer and urbanist who offers lectures and consults to planners, students and decision-makers across Canada, USA and England. Montgomery purpose consists of helping citizens in transform their relationships with each other and their cities using a fusion of different disciplines and content: psychology, neuroscience, urban planning and Montgomery' s social experiments.

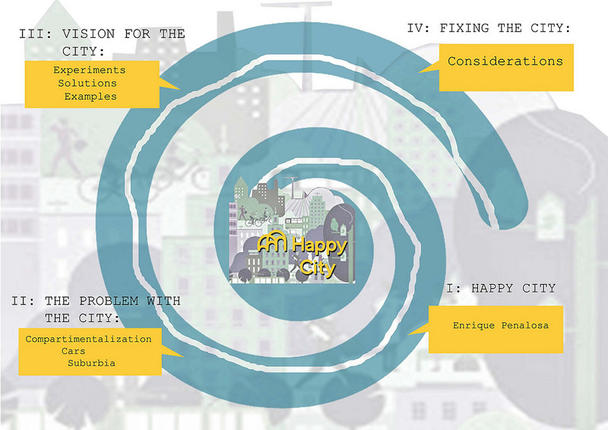

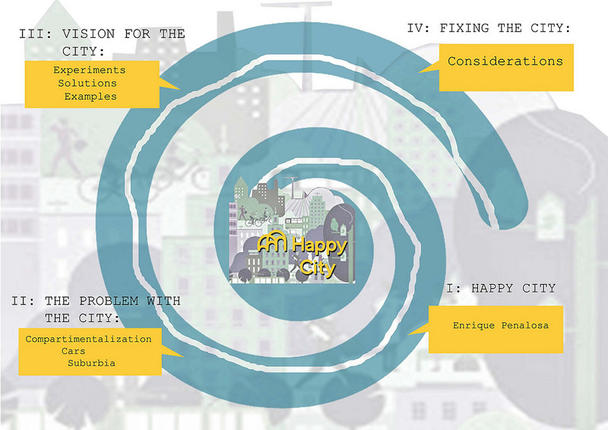

Montgomery's book is characterized by a spiral structure composed of four parts: the first chapter is about the politician Enrique Peñalosa, positive example for territorial administration; the second part introduces possible problems and data analysis about the modern city; the third one is focused on experiments and solutions; the fourth chapter consists of considerations about the happy city, returning to the starting point.

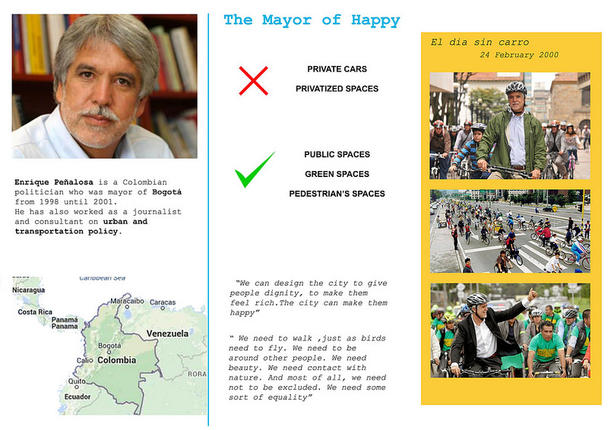

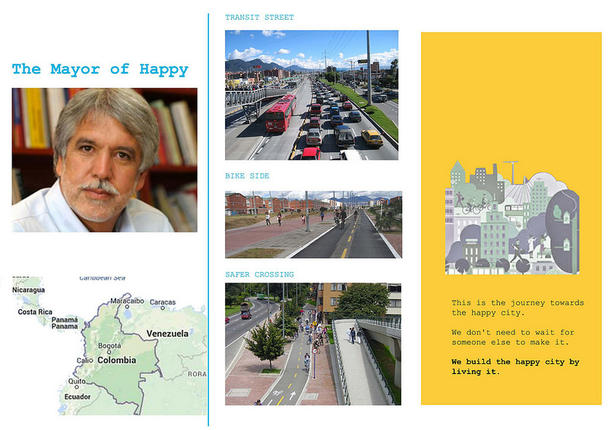

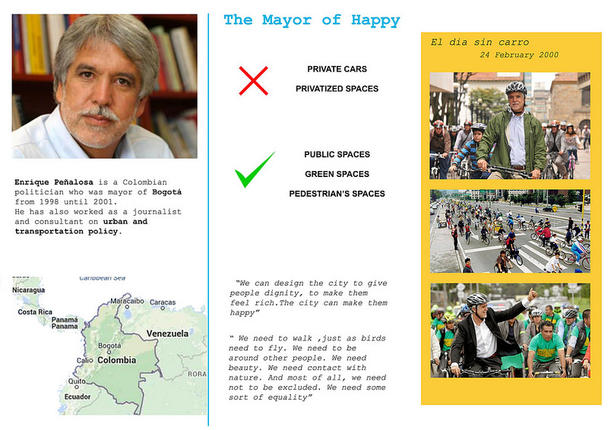

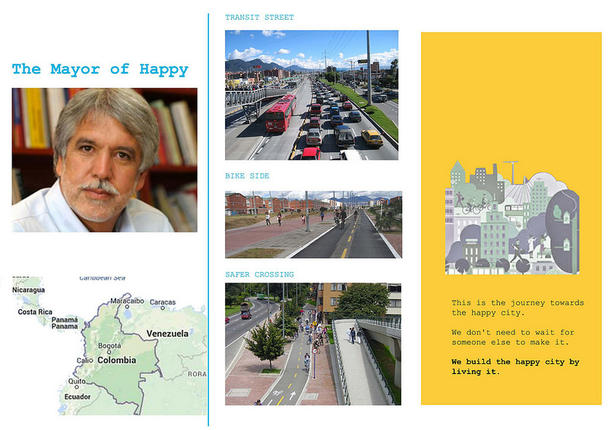

Enrique Peñalosa is a Colombian politician who was mayor of Bogotà from 1998 until 2001 and was re-elected in 2015. He has been involved in urban and transportation planning not only as politician but also as journalist and consultant.

Peñalosa believes in the importance of understanding the relationship between urban planning, political decisions and the life of citizens, as he explains in his speeches:

(“We can design the city to give people dignity, to make them feel rich. The city can make them happy”

“We need to walk , just as birds need to fly. We need to be around other people. We need beauty. We need contact with nature. And most of all, we need not to be excluded. We need some sort of equality”) I would not write it again because it's already written on the slide, but it's up to you.

Peñalosa tried to solve the two main problems of Bogotà city: the million private cars that everyday cross the city and the privatization of the public spaces by cars and mobile vendors, that took over public plazas and pavements.

According to his idea “A city can be friendly to people or it can be friendly to cars, but it can't be both!”, that's the reason why he declared war to private transports and, on the 24th February 2000, he banned all private cars from the city street for a day. The experiment was called “El dia sin carro”, the day without cars, and it was completely successful: citizens of Bogotà could walk in the streets or ride their bicycles. The face of the city changed for one day: it was silent and empty. And the people were so happy.

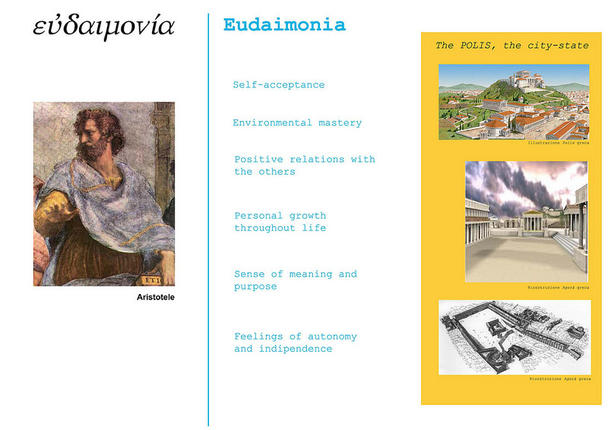

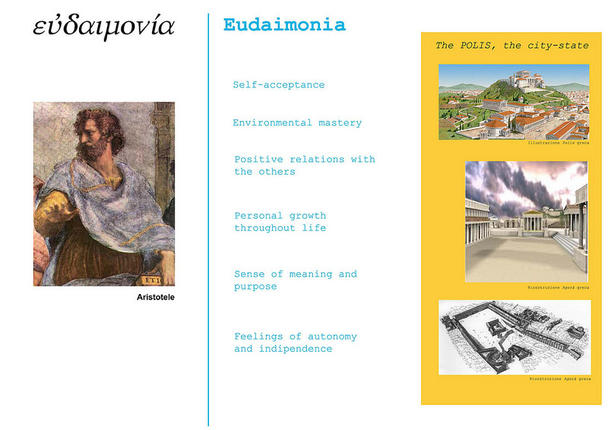

Peñalosa's HAPPY CITY idea is not new: it has an origin in Erodoto's and Aristotle's philosophy, that introduced the concept of “Eudaimonia”. This word is composed by “eu”, translated as “good”, and “daimon”, “demon” in the ancient Greek acceptation: a consciousness or genius, so “to be with a good demon”. This word means something more than “be happy”: it is the realization of our potential and our abilities, and conquer a good position and a consciousness in the world.

The Greek polis, the city-state, was based on this concept. The city was more than a machine for delivering everyday needs., it was an idea that bound together Athenian culture, politics, mores and history. It was the only vehicle that could lead a man to achieve eudaimonia. The agora was not only a square but an invitation to participate in the polis' life.

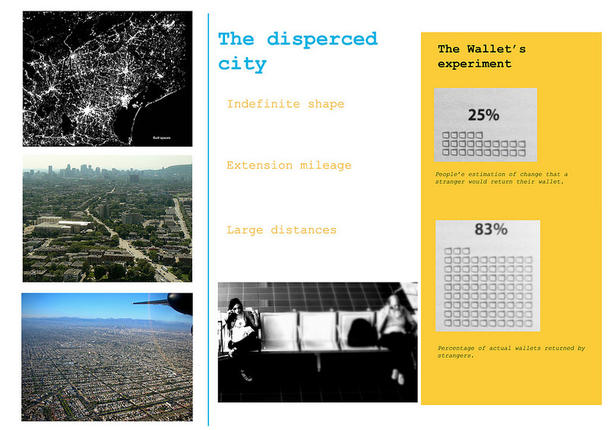

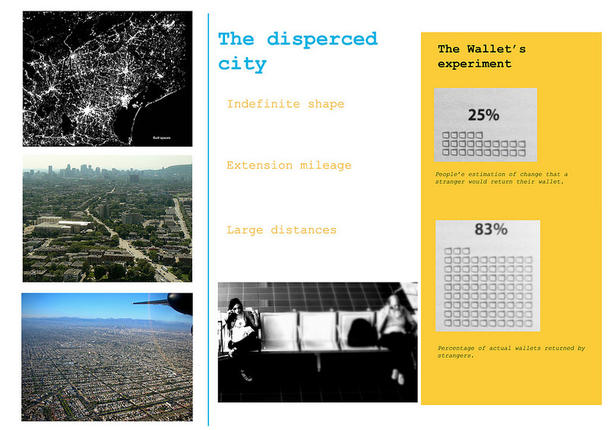

Montgomery found the reasons for the problems in the shape of the modern city, that he calls “dispersed city”.

The city does not have a real border: it extends itself for kilometres and kilometres and this forces inhabitants into using cars and lose the human contact because of the distance. Montgomery lead the Toronto experiment to prove that human relationships are not completely lost despite the „dispersed city theory”: the experiment verifies that while only the 25% of the people think that strangers would return a lost wallet, the likelihood of return was closer to 80%.

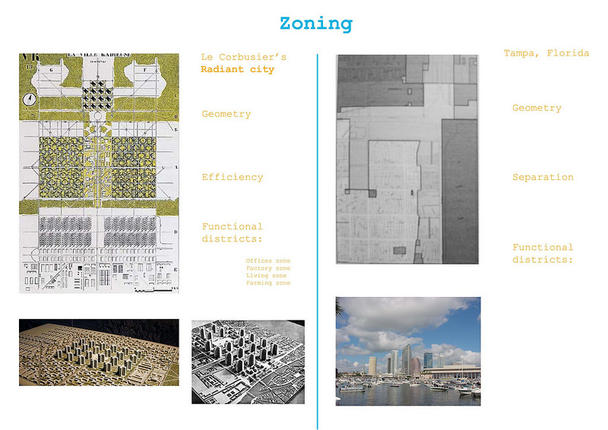

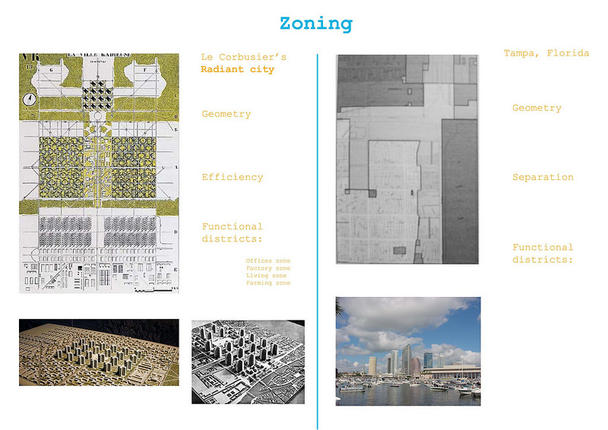

The causes of the structure of our cities are due to the Zoning phenomenon, the planning method used after the second World War, based on laws and development codes that specify what and how you can build: from the lot dimensions to houses typologies.

These codes originate themselves from Le Corbusier's happiness formula: a matter of geometry and efficiency. He believed that most urban problem could be fixed by separating the city into functionally pure districts arranged according to the simple, rational diagrams of the master architect. Those are the fundamentals of his Radiant City plan, where each function is located in a quadrant. This scheme was applied in Tampa (Florida): the ideology of separation lives in American suburban plan. This zoning map reveals a simplistic range of zones that restrict exactly what we can build and what can happen, everywhere.

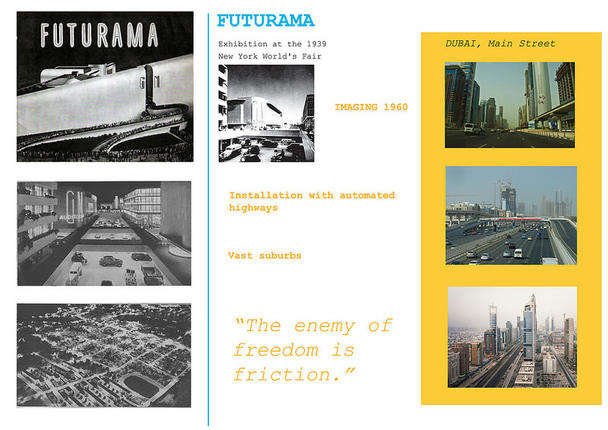

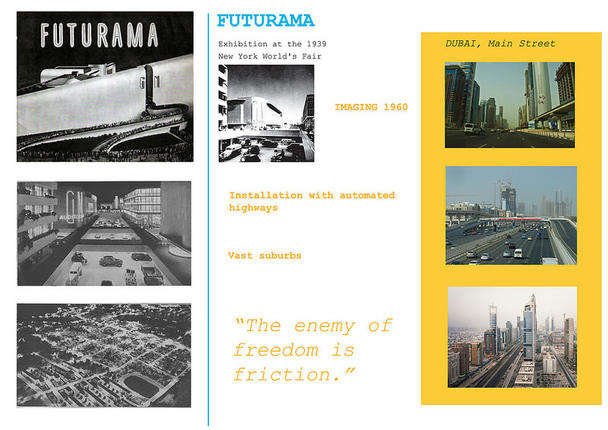

FUTURAMA was an exhibition at the 1939 New York World's Fair designed by Norman Bel Geddes that presented a possible model of the world 20 years into the future (1960). Sponsored by the General Motors Corporation, the installation was characterized by its automated highways and vast suburbs.

Cars, and only cars, were free to move very quickly, independent of all the other things that used to happen on streets. The enemy of freedom, they declared, was friction. Futurama vision has been built into cities around the world, in Dubai for example.

Despite the fact that we live in an era of wealth, we are unhappy, we do not trust our neighbour, we do not communicate with other people and many people take refuge in drugs.

Life satisfaction is strongly influenced by location.: people in small town are generally happier than who live in big cities. People who live next the ocean report being happier than those who don't.

But today EUDAIMONIA is a difficult goal to achieve.

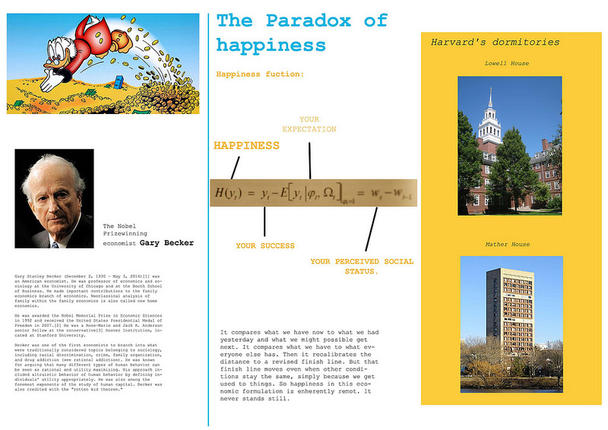

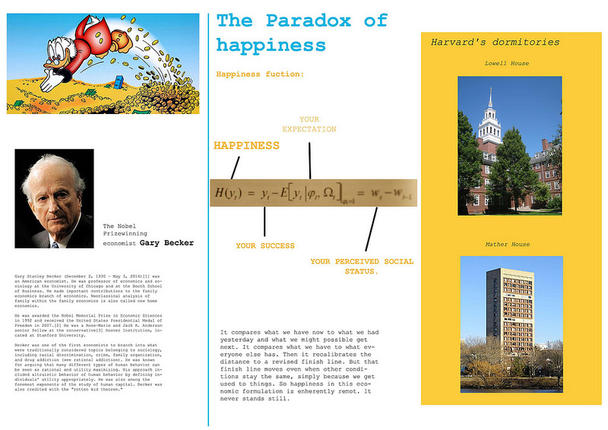

The Nobel Prizewinning economist Gary Becker and his colleague Luis Rayo at the University of Chicago had poured the latest findings in psychology, evolutionary theory, and brain science into an algorithm. The evolutionary happiness function is:

„happiness“ = “your success“ minus “your expectation“= “your perceived social status”.

The formula is a comparison of what we have, what we used to have and what it's possible we will have in the future It compares what we have to what everyone else has. Then it recalibrates the distance to a revised finish line. But that finish line moves even when other conditions stay the same, simply because we get used to things. So happiness in this economic formulation is inherently remote. It never stands still.

Another interesting experiment is about the Harvard's dormitories. There are two: the most prestigious, Lowell House, with its grand redbrick facades, is a classic example of Georgian Revival Style and the other one, Mather House, built in the 70s, is a concrete tower that the student called The Harvard Criminos. Endured the housing lottery in 1996 a lot of students wanted to go to Lowell House but it was not possible for all. they were convinced that the place had the power to make or break their happiness. BUT the results would surprise many Harvard freshmen. Students sent to what they were sure would be miserable house ended up much happier than they had expected while students who landed in the most desirable houses were more miserable than they expected to be.

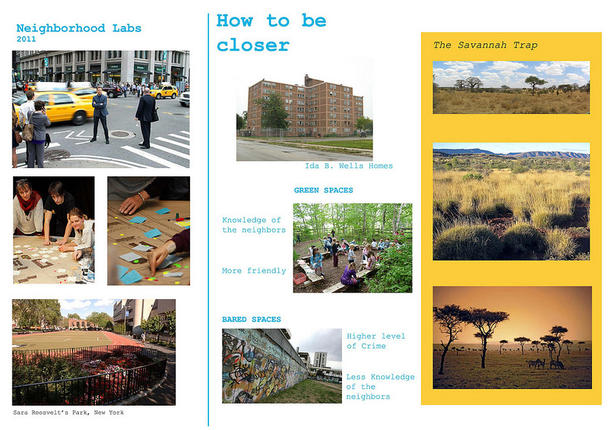

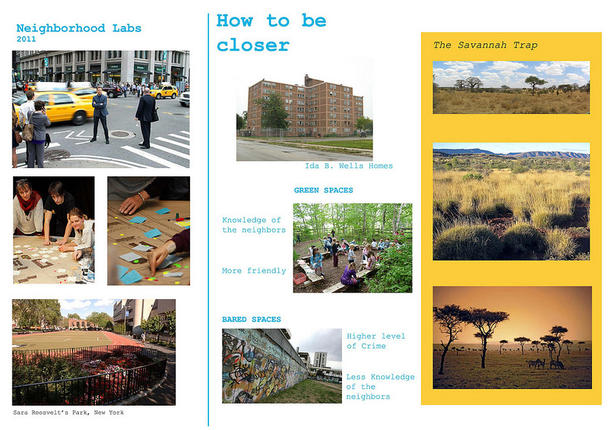

In 2011, Montgomery was invited by the Guggenheim Museum of New York city to lead an experiment: The Lab's neighbourhood, with Collin Ellard, a psychologist at the University of Waterloo.

He equipped dozens of volunteers with devices to measure the emotional state as they moved through the neighbourhood, controlling their levels of affect and also controlling their relative electrical conductance of their skin as they moved.

People reported the biggest spike in happiness just moments after entering in Sara Roosevelt Park.

This did not surprise them: citizens need green spaces. It is also proved that hospital patients with a view of nature need less pain medication and recover faster. Students have better performance on tests when nature is within range.

In the 90s, Ming Kou and Sullivan analysed the project of Ida Well. It is low-rise social housing complex in Chicago It is composed of many and complex courtyards: some bare and in concrete and some with green, flowerbeds and benches. People who lived next the green spaces knew more of their neighbours and they were more friendly.

There are a lot of data that illustrate that the building that looked out on trees and grass experienced about half of the violent crime level of buildings that looked ours on barren courtyards.

Psychologists believe the Savannah-like view have an inherently calming effect on us. Evolutionary theorists argue that we are genetically inclined to like such landscapes because liking them helped our Palaeolithic ancestors survive.

Humphry Repton, a landscape architect who designed the most of the important garden in England in 18th century had understood this ancestral link.

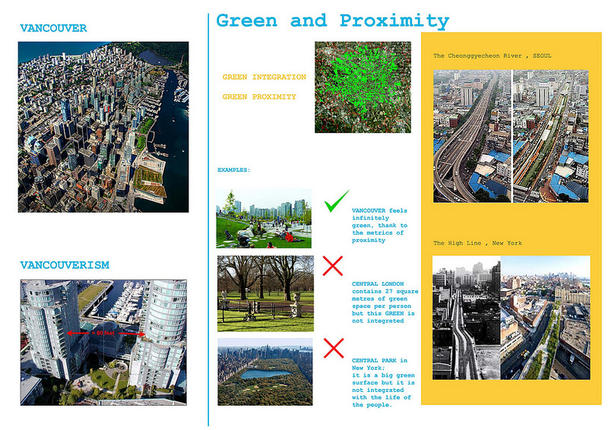

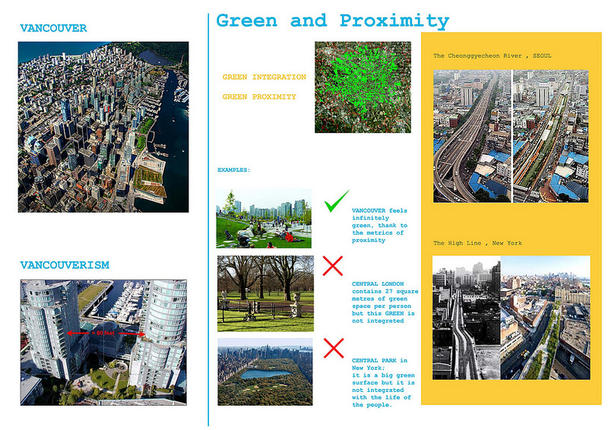

VANCOUVER

That made Vancouver is the only major city in North America without a single highway running through its core and it has also the lowest per capita carbon footprint of any major city on the continent. The reason why the city has no highway is due to a refusal from the citizens, who rejected the proposed plan.

City planners have responded with laws that define the skyline, creating a series of “open-view axes” throughout the city that allows seeing the mountain landscape from several points.

To allow this effect Vancouver has a vertical design: several levels of shops and services would typically be combined with blocks that also have the function of podium for residential five, six or more residential towers, divided by a minimum distance of 80 feet (25 meters). This vertical city model is so typical of Vancouver that the concept model took his name from the city: in fact, it is called Vancouverism.

It is not possible to deny the benefit of an expansive nature view, but the only presence of green spaces is not enough. In fact, it is really important a careful planning of the green area position and their integration in the city: proximity is the key word we need to remember. Central London, for example, contains 27 square metres of green space per person, almost a third more than Vancouver, but the American city feels infinitely more green, thank the metrics of proximity. The same for Central Park in New York; it is a big green surface but it is not integrated with the life of inhabitants.

-The modern example was set in 2005 in Seoul in Korea when Myung Bak, the mayor, demolished five miles of elevated downtown freeway to restore daylight to the ancient waterway. Liberated from the concrete shadow, the Cheonggyecheon River is a popular park where during the summer millions of people come and linger out in nature.

-The other project is the HIGH LINE, the decommissioned elevated rail line converted into a 19 block linear park on Manhattan West Side.

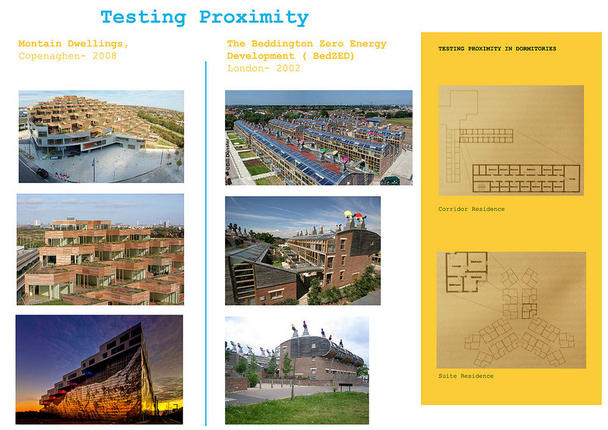

TESTING PROXIMITY

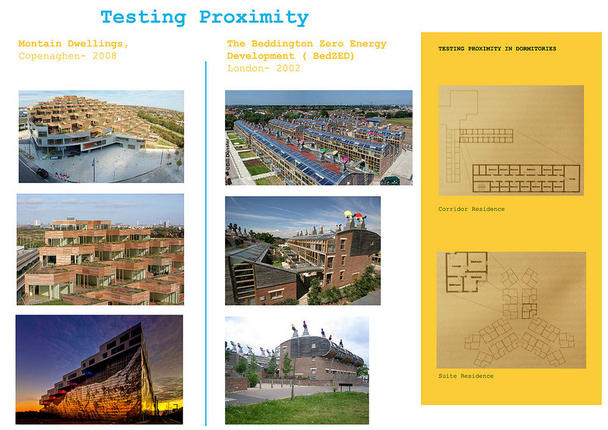

Andrew Baum, in 1973, compared the behaviour of residents of two strongly different college dormitories at Stony Brook University in Long Island, New York.

In the first residence, 34 students used to live in double bedrooms along a single long corridor, sharing one large bathroom and a lounge area at the end of the hallway.

The second building housed the same number of students, but the floor was split into small apartments, with two or three bedrooms each sharing a long and small bathroom. All the students were randomly assigned.

The students who lived in the “corridor block” felt crowded and stressed out and they complained about unwanted social interactions. The corridor was a strong line with no filter space. Students were either in their room or out in the public area. The corridor residents did not become friends as the suite residents did. The corridor residents were less helpful to one another and they were more antisocial.

For a good living experience, we need privacy, nature, conviviality, and convenience. We need a hybrid space, somewhere between the vertical and horizontal city.

In Copenhagen, Bjarke Ingels Group designed Mountain Dwellings: 80 apartments with patios over eleven stocks of sloping roof on the top of a neighbourhood parking lot.

The Beddington Zero Energy Development in London aggressively mixed housing with workshops and offices. Because of many residents actually work in the complex Bed ZED has traded a third of its car parking spaces for a public garden.

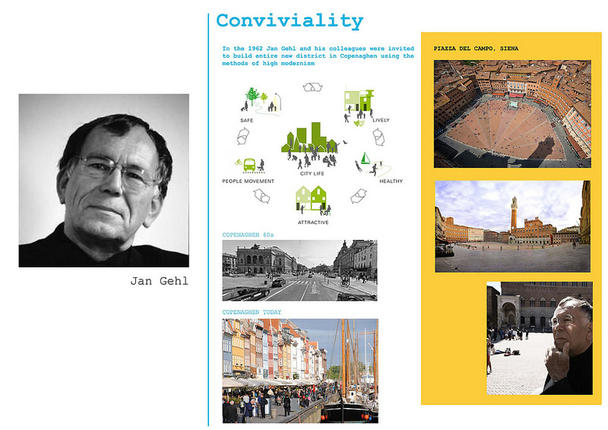

CONVIVIALITIES

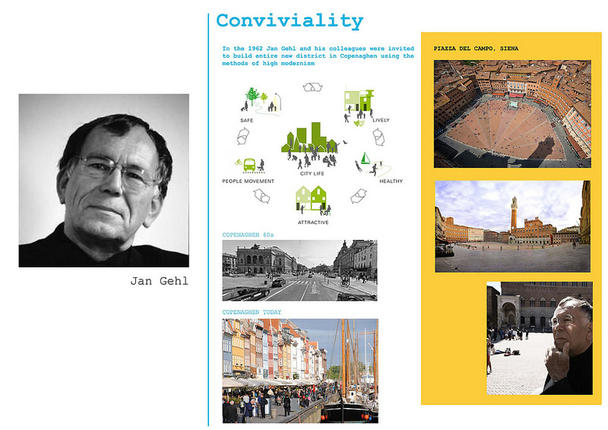

In 1962, Jan Gehl and his colleagues were invited to build a whole new district in Copenhagen using the methods of high modernism. Gehl's wife, a psychologist, criticized their approach asserting that architects rarely considered their neighbourhood’s relationships. Trying to solve the problem they tried to understand human activity between buildings in cities, analysing Italian medieval town models.

As consequence, they began to study the medieval towns of Italy. They were interesting about the human activity between building in cities and town that had not yet been reorganized by rational planners or invaded by cars.

They began to analyze the “Piazza del Campo”, in Siena. They wanted to understand why this place is so special: inhabitants like lingering out there and drinking coffee, walking around the square. “Piazza del Campo” drew the people together.

In 1962, the Copenhagen's City Council decided to lead an experiment banning cars from the spine of the city centre. The initiative bordered Danish population who asserted that what they need are far from the Italian ones: they do not use to sit in outdoor café, drinking cappuccino or espresso, they do not need a free car city centre.

Gehl began to observe people, from child to elderly people, behaviour. The idea was to study the cycle of their life: from the day to the year.

Gehl ended up planning the Copenhagen's University district, with a pedestrian area as most important

point.

Copenhagen did change: the free car streets are nowadays full of bike riders and the city is dominated by the pedestrian's life. Copenhagen's citizens changed, they sit in the square or linger out in the street drinking cappuccino (they are a little bit more Italian now). The reason for this improvement is that each plaza, park or architectural facade sends messages about who we are and what the street is for. We don't need to build a spectacular architecture but we need to understand what people need.

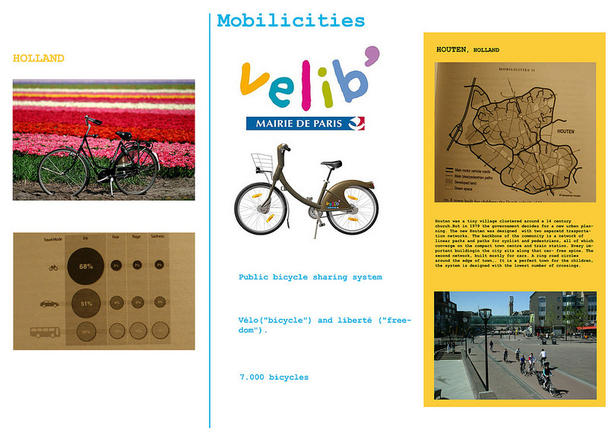

MOBILICITIES

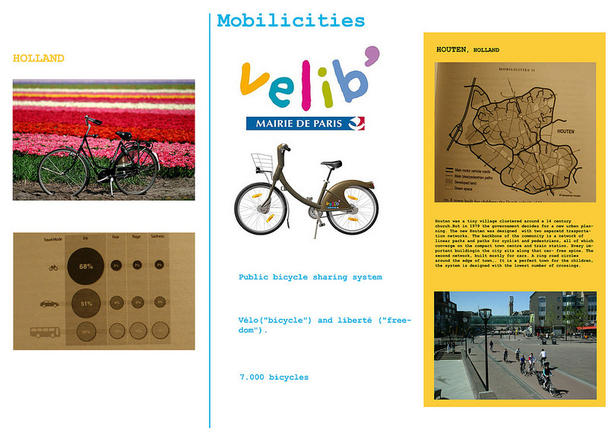

Netherland is the country with the highest number of bike side in the world. Road designers create safe spaces for bikes, cyclist report feeling more joy, less fear, less anger, less sadness than both drivers and transit users.

According to the theory that we were born to move, and that our genetic forebears have been walking for four million years, it should be natural to walk. On the other hand, it is a fact that inhabitants do not enjoy walking across the city, and it is maybe possible to find the answer in the city structure: lot of people are simply too scared to walk or ride bicycles in traffic, the problem could be also the pollution or the “modern unhappiness”. Studies did not verify yet this theory and the reason is still a real enigma.

MOBILICITIES II. INITIATIVES

«Vélib» is a large-scale public bicycle sharing service in Paris, France. The name itself is composed of two French words: vélo ("bicycle") and liberté ("freedom").

The initiative was proposed by Paris mayor and Bertrand Delanoë. The system was launched on 15 July 2007: 7,000 bicycles were initially introduced to the city, distributed among 750 automated rental stations, with fifteen or more bicycle parking slots each.

It offers a new kind of freedom for anyone willing to share space and equipment. “Vélib” is more than a tool of convenience, it embodies a new social and political philosophy.

Houten (Netherlands) used to be a tiny village clustered around a 14-century church, until, in 1979, the government changed the urban plan: the new Houten was designed with two separate transportation networks. The fundament of the community is a web of linear parks and paths for cyclist and pedestrians, each path converges to the compact town centre and train station. The second network, built mostly for cars, consist of a road circle road around the edge of town.

FINALLY, HE RETURNS TO STARTING POINT

In the last chapter, Montgomery came back to the starting point: Enrique Peñalosa, the man who changed the face of Bogotà, organized several initiatives and projects: from transit street to side way. He supports the theory that the sidewalks quality is the index to define the evolution of a city.

This is the journey towards the happy city. We don't need to wait for someone else to make it. We build the happy city by living it.

The author is a Canadian writer and urbanist who offers lectures and consults to planners, students and decision-makers across Canada, USA and England. Montgomery purpose consists of helping citizens in transform their relationships with each other and their cities using a fusion of different disciplines and content: psychology, neuroscience, urban planning and Montgomery' s social experiments.

Montgomery's book is characterized by a spiral structure composed of four parts: the first chapter is about the politician Enrique Peñalosa, positive example for territorial administration; the second part introduces possible problems and data analysis about the modern city; the third one is focused on experiments and solutions; the fourth chapter consists of considerations about the happy city, returning to the starting point.

Enrique Peñalosa is a Colombian politician who was mayor of Bogotà from 1998 until 2001 and was re-elected in 2015. He has been involved in urban and transportation planning not only as politician but also as journalist and consultant.

Peñalosa believes in the importance of understanding the relationship between urban planning, political decisions and the life of citizens, as he explains in his speeches:

(“We can design the city to give people dignity, to make them feel rich. The city can make them happy”

“We need to walk , just as birds need to fly. We need to be around other people. We need beauty. We need contact with nature. And most of all, we need not to be excluded. We need some sort of equality”) I would not write it again because it's already written on the slide, but it's up to you.

Peñalosa tried to solve the two main problems of Bogotà city: the million private cars that everyday cross the city and the privatization of the public spaces by cars and mobile vendors, that took over public plazas and pavements.

According to his idea “A city can be friendly to people or it can be friendly to cars, but it can't be both!”, that's the reason why he declared war to private transports and, on the 24th February 2000, he banned all private cars from the city street for a day. The experiment was called “El dia sin carro”, the day without cars, and it was completely successful: citizens of Bogotà could walk in the streets or ride their bicycles. The face of the city changed for one day: it was silent and empty. And the people were so happy.

Peñalosa's HAPPY CITY idea is not new: it has an origin in Erodoto's and Aristotle's philosophy, that introduced the concept of “Eudaimonia”. This word is composed by “eu”, translated as “good”, and “daimon”, “demon” in the ancient Greek acceptation: a consciousness or genius, so “to be with a good demon”. This word means something more than “be happy”: it is the realization of our potential and our abilities, and conquer a good position and a consciousness in the world.

The Greek polis, the city-state, was based on this concept. The city was more than a machine for delivering everyday needs., it was an idea that bound together Athenian culture, politics, mores and history. It was the only vehicle that could lead a man to achieve eudaimonia. The agora was not only a square but an invitation to participate in the polis' life.

Montgomery found the reasons for the problems in the shape of the modern city, that he calls “dispersed city”.

The city does not have a real border: it extends itself for kilometres and kilometres and this forces inhabitants into using cars and lose the human contact because of the distance. Montgomery lead the Toronto experiment to prove that human relationships are not completely lost despite the „dispersed city theory”: the experiment verifies that while only the 25% of the people think that strangers would return a lost wallet, the likelihood of return was closer to 80%.

The causes of the structure of our cities are due to the Zoning phenomenon, the planning method used after the second World War, based on laws and development codes that specify what and how you can build: from the lot dimensions to houses typologies.

These codes originate themselves from Le Corbusier's happiness formula: a matter of geometry and efficiency. He believed that most urban problem could be fixed by separating the city into functionally pure districts arranged according to the simple, rational diagrams of the master architect. Those are the fundamentals of his Radiant City plan, where each function is located in a quadrant. This scheme was applied in Tampa (Florida): the ideology of separation lives in American suburban plan. This zoning map reveals a simplistic range of zones that restrict exactly what we can build and what can happen, everywhere.

FUTURAMA was an exhibition at the 1939 New York World's Fair designed by Norman Bel Geddes that presented a possible model of the world 20 years into the future (1960). Sponsored by the General Motors Corporation, the installation was characterized by its automated highways and vast suburbs.

Cars, and only cars, were free to move very quickly, independent of all the other things that used to happen on streets. The enemy of freedom, they declared, was friction. Futurama vision has been built into cities around the world, in Dubai for example.

Despite the fact that we live in an era of wealth, we are unhappy, we do not trust our neighbour, we do not communicate with other people and many people take refuge in drugs.

Life satisfaction is strongly influenced by location.: people in small town are generally happier than who live in big cities. People who live next the ocean report being happier than those who don't.

But today EUDAIMONIA is a difficult goal to achieve.

The Nobel Prizewinning economist Gary Becker and his colleague Luis Rayo at the University of Chicago had poured the latest findings in psychology, evolutionary theory, and brain science into an algorithm. The evolutionary happiness function is:

„happiness“ = “your success“ minus “your expectation“= “your perceived social status”.

The formula is a comparison of what we have, what we used to have and what it's possible we will have in the future It compares what we have to what everyone else has. Then it recalibrates the distance to a revised finish line. But that finish line moves even when other conditions stay the same, simply because we get used to things. So happiness in this economic formulation is inherently remote. It never stands still.

Another interesting experiment is about the Harvard's dormitories. There are two: the most prestigious, Lowell House, with its grand redbrick facades, is a classic example of Georgian Revival Style and the other one, Mather House, built in the 70s, is a concrete tower that the student called The Harvard Criminos. Endured the housing lottery in 1996 a lot of students wanted to go to Lowell House but it was not possible for all. they were convinced that the place had the power to make or break their happiness. BUT the results would surprise many Harvard freshmen. Students sent to what they were sure would be miserable house ended up much happier than they had expected while students who landed in the most desirable houses were more miserable than they expected to be.

In 2011, Montgomery was invited by the Guggenheim Museum of New York city to lead an experiment: The Lab's neighbourhood, with Collin Ellard, a psychologist at the University of Waterloo.

He equipped dozens of volunteers with devices to measure the emotional state as they moved through the neighbourhood, controlling their levels of affect and also controlling their relative electrical conductance of their skin as they moved.

People reported the biggest spike in happiness just moments after entering in Sara Roosevelt Park.

This did not surprise them: citizens need green spaces. It is also proved that hospital patients with a view of nature need less pain medication and recover faster. Students have better performance on tests when nature is within range.

In the 90s, Ming Kou and Sullivan analysed the project of Ida Well. It is low-rise social housing complex in Chicago It is composed of many and complex courtyards: some bare and in concrete and some with green, flowerbeds and benches. People who lived next the green spaces knew more of their neighbours and they were more friendly.

There are a lot of data that illustrate that the building that looked out on trees and grass experienced about half of the violent crime level of buildings that looked ours on barren courtyards.

Psychologists believe the Savannah-like view have an inherently calming effect on us. Evolutionary theorists argue that we are genetically inclined to like such landscapes because liking them helped our Palaeolithic ancestors survive.

Humphry Repton, a landscape architect who designed the most of the important garden in England in 18th century had understood this ancestral link.

VANCOUVER

That made Vancouver is the only major city in North America without a single highway running through its core and it has also the lowest per capita carbon footprint of any major city on the continent. The reason why the city has no highway is due to a refusal from the citizens, who rejected the proposed plan.

City planners have responded with laws that define the skyline, creating a series of “open-view axes” throughout the city that allows seeing the mountain landscape from several points.

To allow this effect Vancouver has a vertical design: several levels of shops and services would typically be combined with blocks that also have the function of podium for residential five, six or more residential towers, divided by a minimum distance of 80 feet (25 meters). This vertical city model is so typical of Vancouver that the concept model took his name from the city: in fact, it is called Vancouverism.

It is not possible to deny the benefit of an expansive nature view, but the only presence of green spaces is not enough. In fact, it is really important a careful planning of the green area position and their integration in the city: proximity is the key word we need to remember. Central London, for example, contains 27 square metres of green space per person, almost a third more than Vancouver, but the American city feels infinitely more green, thank the metrics of proximity. The same for Central Park in New York; it is a big green surface but it is not integrated with the life of inhabitants.

-The modern example was set in 2005 in Seoul in Korea when Myung Bak, the mayor, demolished five miles of elevated downtown freeway to restore daylight to the ancient waterway. Liberated from the concrete shadow, the Cheonggyecheon River is a popular park where during the summer millions of people come and linger out in nature.

-The other project is the HIGH LINE, the decommissioned elevated rail line converted into a 19 block linear park on Manhattan West Side.

TESTING PROXIMITY

Andrew Baum, in 1973, compared the behaviour of residents of two strongly different college dormitories at Stony Brook University in Long Island, New York.

In the first residence, 34 students used to live in double bedrooms along a single long corridor, sharing one large bathroom and a lounge area at the end of the hallway.

The second building housed the same number of students, but the floor was split into small apartments, with two or three bedrooms each sharing a long and small bathroom. All the students were randomly assigned.

The students who lived in the “corridor block” felt crowded and stressed out and they complained about unwanted social interactions. The corridor was a strong line with no filter space. Students were either in their room or out in the public area. The corridor residents did not become friends as the suite residents did. The corridor residents were less helpful to one another and they were more antisocial.

For a good living experience, we need privacy, nature, conviviality, and convenience. We need a hybrid space, somewhere between the vertical and horizontal city.

In Copenhagen, Bjarke Ingels Group designed Mountain Dwellings: 80 apartments with patios over eleven stocks of sloping roof on the top of a neighbourhood parking lot.

The Beddington Zero Energy Development in London aggressively mixed housing with workshops and offices. Because of many residents actually work in the complex Bed ZED has traded a third of its car parking spaces for a public garden.

CONVIVIALITIES

In 1962, Jan Gehl and his colleagues were invited to build a whole new district in Copenhagen using the methods of high modernism. Gehl's wife, a psychologist, criticized their approach asserting that architects rarely considered their neighbourhood’s relationships. Trying to solve the problem they tried to understand human activity between buildings in cities, analysing Italian medieval town models.

As consequence, they began to study the medieval towns of Italy. They were interesting about the human activity between building in cities and town that had not yet been reorganized by rational planners or invaded by cars.

They began to analyze the “Piazza del Campo”, in Siena. They wanted to understand why this place is so special: inhabitants like lingering out there and drinking coffee, walking around the square. “Piazza del Campo” drew the people together.

In 1962, the Copenhagen's City Council decided to lead an experiment banning cars from the spine of the city centre. The initiative bordered Danish population who asserted that what they need are far from the Italian ones: they do not use to sit in outdoor café, drinking cappuccino or espresso, they do not need a free car city centre.

Gehl began to observe people, from child to elderly people, behaviour. The idea was to study the cycle of their life: from the day to the year.

Gehl ended up planning the Copenhagen's University district, with a pedestrian area as most important

point.

Copenhagen did change: the free car streets are nowadays full of bike riders and the city is dominated by the pedestrian's life. Copenhagen's citizens changed, they sit in the square or linger out in the street drinking cappuccino (they are a little bit more Italian now). The reason for this improvement is that each plaza, park or architectural facade sends messages about who we are and what the street is for. We don't need to build a spectacular architecture but we need to understand what people need.

MOBILICITIES

Netherland is the country with the highest number of bike side in the world. Road designers create safe spaces for bikes, cyclist report feeling more joy, less fear, less anger, less sadness than both drivers and transit users.

According to the theory that we were born to move, and that our genetic forebears have been walking for four million years, it should be natural to walk. On the other hand, it is a fact that inhabitants do not enjoy walking across the city, and it is maybe possible to find the answer in the city structure: lot of people are simply too scared to walk or ride bicycles in traffic, the problem could be also the pollution or the “modern unhappiness”. Studies did not verify yet this theory and the reason is still a real enigma.

MOBILICITIES II. INITIATIVES

«Vélib» is a large-scale public bicycle sharing service in Paris, France. The name itself is composed of two French words: vélo ("bicycle") and liberté ("freedom").

The initiative was proposed by Paris mayor and Bertrand Delanoë. The system was launched on 15 July 2007: 7,000 bicycles were initially introduced to the city, distributed among 750 automated rental stations, with fifteen or more bicycle parking slots each.

It offers a new kind of freedom for anyone willing to share space and equipment. “Vélib” is more than a tool of convenience, it embodies a new social and political philosophy.

Houten (Netherlands) used to be a tiny village clustered around a 14-century church, until, in 1979, the government changed the urban plan: the new Houten was designed with two separate transportation networks. The fundament of the community is a web of linear parks and paths for cyclist and pedestrians, each path converges to the compact town centre and train station. The second network, built mostly for cars, consist of a road circle road around the edge of town.

FINALLY, HE RETURNS TO STARTING POINT

In the last chapter, Montgomery came back to the starting point: Enrique Peñalosa, the man who changed the face of Bogotà, organized several initiatives and projects: from transit street to side way. He supports the theory that the sidewalks quality is the index to define the evolution of a city.

This is the journey towards the happy city. We don't need to wait for someone else to make it. We build the happy city by living it.